EDITOR’S NOTE: Because, for the first time in a year and a half, both professional and personal responsibilities precluded my producing a post for Science-Based Medicine, today is the perfect time to present a guest post by Ben Kavoussi. Ben is a medical informatician with an interest in the scientific evaluation of CAM, as well as a Captain in the Army Medical Service Corps. He also studied to become an acupuncturist himself, and his article is a fascinating look at some little known history behind acupuncture that strongly suggests that it is more akin to astrology than you may be aware of. Certainly I had been unaware of it, and I bet most of our readers are unaware of it, too.

Enjoy!

I’ll be back with a post here next week at the latest.

Astrology with Needles

by Ben Kavoussi, MS, MSOM, LAc

The following is an excerpt of an upcoming article called “The Untold Story of Acupuncture.” It is scheduled to be published in December 2009 in Focus in Alternative and Complementary Therapies (FACT), a review journal that presents the evidence on alternative medicine in an analytical and impartial manner. It argues that if the effects of “real” and “sham” acupuncture do not significantly differ in well-conducted trials, it is because traditional theories for selecting points and means of stimulation are not based on an empirical rationale, but on ancient cosmology, astrology and mythology. These theories significantly resemble those that underlined European and Islamic astrological medicine and bloodletting in the Middle-Ages. In addition, the alleged predominance of acupuncture amongst the scholarly medical traditions of China is not supported by evidence, given that for most of China’s long medical history, needling, bloodletting and cautery were largely practiced by itinerant and illiterate folk-healers, and frowned upon by the learned physicians who favored the use of pharmacopoeia.

Heaven is covered with constellations, Earth with waterways, and man with channels.

Acupuncture is presumed to have its origins in blood ritual, magic tattooing and body piercing associated with Neolithic healing practices.2,3 The Neolithic origin hypothesis is supported by the presence of nonfigurative tattoos on the Tyrolean Ice Man–an inhabitant of the Oetztal Alps in Europe–whose naturally preserved 5,200-year-old body displays a set of small cross-shaped tattoos that are located significantly proximal to classical acupuncture points. Medical imaging shows that the middle-aged man suffered from lumbar arthrosis and the cross-shaped tattoos are located at points traditionally indicated for this condition.4,5 Similar nonfigurative tattoos and evidence of therapeutic tattooing, lancing and blood ritual have been found throughout the Ancient world, including the Americas.6,7,8 Health-related tattoos are still prevalent in Tibet, where specific points on the body are needled with a blend of medicinal herbs in the dyes. These practices appear to be largely intended to maintain balance with the natural and spiritual worlds, and also to protect against demonic infestation and malevolence. Seemingly, this Neolithic and Bronze Age lancing heritage, which was intertwined with magic and animism has evolved in various cultures into codified systems of lancing and venesection for assuring good health and longevity. In addition to treating the impurity or superabundance of blood, in various cultures lancing was also believed to affect the flow of a numinous life-force that is, for instance, called qi (or chi, 氣, pronounced “chee”) in Chinese, prāna (प्राण) in Sanskrit, pneuma (πνεύμα) in Greek, etc.9 In many instances, elements of metaphysics, mythology, mysticism, magic, shamanism, exorcism, astrology and empirical medicine intimately intertwined, making it difficult for modern scholars to interpret them as mutually exclusive categories.

In China, for instance, the numinous force was believed to mirror the Sun’s annual journey through the Ecliptic–meaning its apparent path on the celestial sphere–and to circulate in a network of 12 primary jing luo (經络) known in English as the chinglo channels or simply channels or meridians (a term coined in 1939 by George Soulié de Morant, a French diplomat). These imaginary pathways run from head to toes and interconnect around 360 primary points on the skin.10 There is a strong possibility that the web of these channels was a rudimentary model of the vascular system that was conceptualized according to an episteme–meaning a set of fundamental beliefs–that was based on astrological principles and mythology. This episteme also indicated that a person’s health and destiny are determined by the position of the Sun, the Moon, the 5 Planets and the apparition of comets, along with the person’s time of birth.11 In this worldview, each body segment corresponds to one of the 12 Houses of the Chinese zodiac system di zhi (地支) known in English as the Earthly Branches, and which consists of 12 two-hour (30°) divisions of the Ecliptic. The channels are therefore named according to their degree of yin (阴) and yang (阳), from tai yang (太阳) to jue yin (厥阴), which are terms that describe the phases and the positions of the Sun and the Moon.12 Each has five special points designated by the characters 水 (Water), 木 (Wood), 火 (Fire), 土 (Earth) and 金 (Metal) which are also the Chinese terms for Mercury, Jupiter, Mars, Saturn and Venus,13 and seem to correspond to the transit positions of these Planets in the matching House. Each point is also associated with a color, which comes from the visual appearance of the matching Planet in the night sky. Venus is white, Jupiter blue-green, Saturn golden-yellow, Mars red, and Mercury “black,” for it appears to be the dimmest of the five. Each of these points has also an occult connection with a direction, a segment of time, a season, a number set, a taste, a musical note, an internal organ, a body region, etc, in an ancient Chinese metaphysical cosmology often referred to as “correlative cosmology”14 and reminiscent of the esoteric and mystical beliefs held by Pythagoras of Samos (c. 580-c. 490 BC) and his followers, the Pythagoreans.15 In his occult and magico-mystical worldview, the nature of the life-force qi is often described in such terms:16

The major premise of Chinese medical theory is that all the forms of life in the universe are animated by an essential life-force or vital energy called qi. Qi also means “breath” and air and is similar to the Hindu concept of prāna. Invisible, tasteless, odorless, and formless, qi nevertheless permeates the entire cosmos. Qi is transferable and transmutable; digestion extracts qi from food and drink and transfers it to the body, breathing extracts qi from air and transfers it to the lungs. When these two forms of qi meet in the blood-stream, they transmute to form human-qi, which then circulates throughout the body as vital energy. It is the quality and balance of your qi that determines your state of health and span of life.

Other texts refer to qi as a “cosmic spirit that pervades and enlivens all things”17 and “from which the world was created.”18 For instance, the alchemist Ko Hung (葛洪, 2nd – 3rd Century AD) writes that “Man is in qi and qi is in each human being. Heaven and Earth and the ten thousand things all require qi to stay alive. A person that knows how to allow qi to circulate will preserve himself and banish illness that might cause him harm.”19, 20 The belief in a “cosmological correlation” between its pathways in the body and the Houses of the Chinese zodiac seems to be based on health and safety beliefs in geocentric cosmology and the related doctrine of “as above, so below” which stipulated that everything in the Heavens has its counterpart on Earth and also in man.

The episteme of “as above, so below” and correlative cosmology were prevalent throughout the ancient world, from the Eastern Mediterranean cultures to Northern Europe. It is notably found in the relics of a collection of occult writings called the Corpus Hermetica which are believed to be compiled in Hellenistic Egypt during the 1st or 3rd century AD and are attributed to Hermes Trismegistus (“Thrice-great Hermes”), the Greek equivalent of the Egyptian god of wisdom, Thoth. The original text was presumably lost or destroyed during the systematic annihilation of non-Christian literature between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. Nonetheless, a section of it known as the Emerald Tablet survived and was translated into Arabic by the Muslim conquerors and later into Latin by John of Seville c. 1140 AD and by Philip of Tripoli c. 1243 AD. An Arabic version of the Tablet by the Muslim polymath and alchemist Abu Musa Jābir ibn Hayyān (أبو موسى جابر بن حيان , c. 721-c. 815 AD) states “That which is above is from that which is below, and that which is below is from that which is above, working the miracles of One.”21 Given the prevalence of this set of fundamental beliefs throughout the ancient world, it seems that the natural philosophy that has given rise to the underlying theories of acupuncture in China stems from the same set of beliefs in that were also prevalent along the Silk Road in Persia, Mesopotamia, Egypt and in Greece and that have influenced the health and safety beliefs of pre-Christian Europe, such as the Eastern Mediterranean mystery cults,22 such as Mithraic Mysteries.23 This hypothesis is supported by a statement by Gregor (Gregorius) Reisch (c. 1467-1525) in Margarita Philosophica (Pearl of Wisdom), first published in 1503:24

The pagans believed that the zodiac formed the body of the Grand Man of the Universe. This body, which they called the Macrocosm (the Great World), was divided into twelve major parts, one of which was under the control of the celestial powers reposing in each of the zodiacal constellations. Believing that the entire universal system was epitomized in man’s body, which they called the Microcosm (the Little World), they evolved that now familiar figure of “the cut-up man in the almanac” by allotting a sign of the zodiac to each of twelve major parts of the human body.

Figure 1: European medieval Zodiac Man form John de Foxton’s Liber Cosmographiae, published in 1408. It indicated the repartition of astrological influences on the body which physicians used to determine the auspicious time to let blood. Images courtesy of The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, UK.

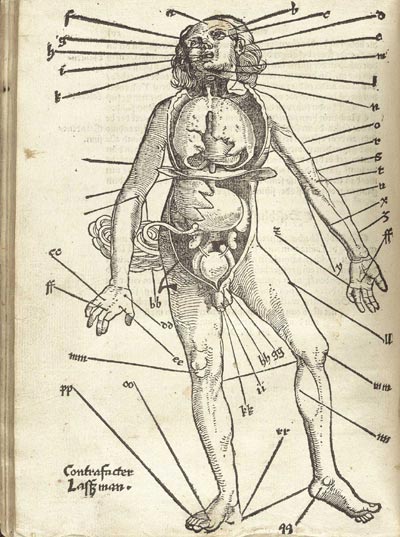

Given this fundamental belief, European physicians until the 17th Century based the practice of medicine on celestial computations, also known as Iatromathematics, astrological medicine or astromedicine. They therefore utilized planetary transition tables called ephemerides or Alfonsine tables to cast a prognostication–meaning a disease outcome prediction based on astrological conjunctions, alignments and the angle between Planets (Aspects)–prior to perform venesection, cupping, cautery, surgery or to prescribe medicines with specific astral powers.25 Disease was then believed to result from interruptions to the flow of the numinous life-force pneuma and an imbalance in the four humors--blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm–which were each associated to an Element, a Planet, a color, etc, according to European correlative cosmology. Therapy consisted of purging the offending humor and its noxious pressures during favorable Aspects. Most bloodletters would open a vein in the arm, leg or neck with a fine knife called a “lancet.” They would tie off the area with a tourniquet and hold the lancet delicately between thumb and forefinger and strike diagonally or lengthwise into the vein to avoid severing it. They would then collect the blood in a measuring bowl.26 Initially, according to the classical Greek procedure, blood was let from a site near the location of the illness but later physicians drew a smaller amount of blood from a distant site. This procedure not only required the knowledge of the distal cutting points and the precise amount of blood to draw, but also the knowledge of ephemerides to establish the suitable Aspects and timing. Medieval medical manuscripts therefore contained ephemeris charts (volvelles) and the schematic of a body covered with astrological signs, generally known as “Zodiac Man,” which illustrated the specific influences of astrological signs on body parts and organs (Figure 1) and the location of the associated bloodletting points (Figure 2).

Figure 2: European Bloodletting Man from Hans von Gersdorff’s Feldtbüch der Wundartzney, published in 1528. Bloodletting was done by venesection or the application of leeches. Most of these points correspond to key acupuncture points, such as LV3, UB40, SI3, LI4, LI11, SJ3, LU5, etc. Image courtesy of the National Library of Medicine, US.

The allotment of the zodiacs to each of the major parts of the body started at the head with Ares and ran down to the feet, which belonged to Pisces. Cancer was believed to be responsible for diseases of the lungs and the eyes and Scorpio the genital afflictions, for instance.27 The practice of lancing, bloodletting and cupping (الحجامة, hijama) to affect specific organs or to mitigate specific diseases based on a postulated relationship between the internal organs and points on the surface of the skin is still prevalent amongst the Muslims worldwide and nowadays video instructions for it are available, even on YouTube. It is plausible that the same principle is at the origin of acupuncture channels in China28 because the distribution of the regions of astrological influences and the related venesection points portrayed in medieval Islamic and European manuscripts significantly resembles the allocation of master, command, influential, and other key points (Table 1). It is important to note that Greco-Arabic bloodletting was known in China and fragments of Avicenna’s (c. 980 – 1037) Cannon of Medicine (الطب في القانون) were translated during the time of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) and published along with other Persian and Arabic texts in the Hui Hui Yao Fang (回回藥方)–meaning the Prescriptions of the Hui Nation–with much of the text in Arabic.29 The correlation between Chinese acupuncture and bloodletting is further supported by the fact that the Chinese character zhēn (針) etymologically refers to lancing with coarse needles or any sharp object used for scarification, bloodletting and minor surgery.30 In addition, As Paul Unschuld points out, the opening of superficial or deep-lying vessels for bloodletting seems to predate the manipulation of qi with needles.31 However, Linda Barnes, in her fascinating book on how China, the Chinese, and their healing practices were imagined in the West from the late Middle Ages through to the mid-19th Century, also argues that there were “sufficient apparent similarities that an early observer might have been excused for imagining that the Chinese and European practices grew from the same conceptual framework.”32 Although she seems to agree with Paul Unschuld’s assessment that acupuncture emerged as an offshoot of bloodletting, she also notes that the early European observers seem to have misunderstood the ways in which the body itself was conceptualized by the Chinese, and assumed that they were simply using a version inferior of the Greek humoral system, and routinely failed to recognize or value an alternate conceptual universe which, in the long run, made it easier for them to dismiss Chinese understandings of the human body.

|

Western Zodiacs |

Degrees |

Regions – Organs |

Chinese Zodiacs |

Hours |

Meridians - Organs |

|

| Aries | 0°-30° | Head | Tiger | 3AM-5AM | Lung | |

| Taurus | 30°-60° | Neck , throat | Rabbit | 5AM-7AM | Large Intestine | |

| Gemini | 60°-90° | Lungs, arms, shoulders | Dragon | 7AM-9 AM | Stomach | |

| Cancer | 90°-120° | Chest, breasts, stomach | Snake | 9AM-11AM | Spleen | |

| Leo | 120°-150° | Heart, upper back | Horse | 11AM-1PM | Heart | |

| Virgo | 150°-180° | Abdomen, digestive system | Sheep | 1PM-3PM | Small Intestine | |

| Libra | 180°-210° | Kidneys, lumbar region | Monkey | 3PM-5PM | Bladder | |

| Scorpio | 210°-240° | Genitals | Rooster | 5PM-7PM | Kidney | |

| Sagittarius | 240°-270° | Hips, thighs | Dog | 7PM-9PM | Pericardium | |

| Capricorn | 270°-300° | Knees, bones | Pig | 9PM-11PM | San Jiao | |

| Aquarius | 300°-330° | Calves, shins, ankles | Rat | 11PM-1AM | Gallbladder | |

| Pisces | 330°-360° | Feet | Ox | 1AM-3AM | Liver |

Table 1: Similarities between Muslim and medieval astromedicine and traditional acupuncture theory. For instance, LU7, a point on the Lung meridian is the command point of the head and the neck; LI4, an important point on the Large Intestine meridian controls the face and the throat; SP4 on the Spleen meridian is used for the diseases of the chest, breast and the stomach. The Kidney meridian controls the genitals; an important point related to San Jiao (UB39) is found on the knee; one related to Gallbladder (GB40) on the ankle; and the most important points of the Liver meridian, LV2-3 are on the feet, etc.33 Be noted that a two-hour segment is the same time measure than 30°, for the celestial sphere moves by 15° every hour.

Paradoxically, for most of China’s long medical history, lancing, bloodletting, acupuncture and surgery were practiced by itinerant folk-healers and considered a lower class of therapy compared to the use of pharmacopoeia. As the historian Bridie Andrews Minehan describes:34

The lowly acupuncturists engaged in a great deal of minor surgery, and the two specialties of acupuncture (zhenjiu) and external medicine or surgery (waike) overlapped considerably. Illustrations of the nine needles of acupuncture, featured in many handbooks from the late imperial period, depicted scalpel-like knives, cautery irons, and three-edged bodkins for bloodletting and lancing boils, as well as the fine needles we currently associate with acupuncture.

Andrews Minehan also notes that although needling is often cited in the Yellow Emperor’s Canon of Medicine, throughout the history of China relatively little has been written on it elsewhere. Reportedly, by the middle of the second millennium its practice was mostly abandoned, and eventually the Chinese and other Eastern societies took steps to eliminate it altogether.34, 35 In 1822 an edict banned its teaching and practice from the Imperial Medical Academy, the institution that provided physicians to the Court. The Japanese government equally prohibited the practice in 1876.36 The final step in China took place in 1929 when it was literally outlawed.37 However, in the early 1930s a Chinese pediatrician by the name of Cheng Dan’an (承淡安, 1899-1957) proposed that needling therapy should be resurrected because its actions could potentially be explained by neurology. He therefore repositioned the points towards nerve pathways and away from blood vessels-where they were previously used for bloodletting. His reform also included replacing coarse needles with the filiform ones in use today.38 Reformed acupuncture gained further interest through the revolutionary committees in the People’s Republic of China in the 1950s and 1960s along with a careful selection of other traditional, folkloric and empirical modalities that were added to scientific medicine to create a makeshift medical system that could meet the dire public health and political needs of Maoist China while fitting the principles of Marxist dialectics. In deconstructing the events of that period, Kim Taylor in her remarkable book on Chinese medicine in early communist China, explains that this makeshift system has achieved the scale of promotion it did because it fitted in, sometimes in an almost accidental fashion, with the ideals of the Communist Revolution. As a result, by the 1960s acupuncture had passed from a marginal practice to an essential and high-profile part of the national health-care system under the Chinese Communist Party, who, as Kim Taylor argues, had laid the foundation for the institutionalized and standardized format of modern Chinese medicine and acupuncture found in China and abroad today.39 This modern construct was also a part of the training of the “barefoot doctors,” meaning peasants with an intensive three- to six-month medical and paramedical training, who worked in rural areas during the nationwide healthcare disarray of the Cultural Revolution era.40 They provided basic health care, immunizations, birth control and health education, and organized sanitation campaigns. Chairman Mao believed, however, that ancient natural philosophies that underlined these therapies represented a spontaneous and naive dialectical worldview based on social and historical conditions of their time and should be replaced by modern science.41 It is also reported that he did not use acupuncture and Chinese medicine for his own ailments.42

It is the reformed and “sanitized” acupuncture and the makeshift theoretical framework of Maoist China that have flourished in the West as “Traditional,” “Chinese,” “Oriental,” and most recently as “Asian” medicine. Nowadays, in every major metropolitan area in the US and in Europe, one can find acupuncture boutiques where practitioners inaccurately claim that gently puncturing the skin with silicon-coated stainless-steel filiform needles is a scholarly medical tradition of ancient China that has been used for over 2,000 years to relieve pain and to treat a variety of diseases. Meanwhile and despite what is reported by the advocates, this gentle insertion of fine needles at specific points on the skin has consistently failed in well-conducted trials to show compelling evidence of efficacy for conditions that are amenable to specific treatments.43, 44 And whatever the clinical efficacy of any type of needling therapy, there is still no convincing evidence that meridians exist as discrete entities distinct from blood vessels.45

ADDENDUM:

My sincerest apologies to Linda Barnes for citing her work as simply arguing that there are sufficient similarities between needling in China and bloodletting in Europe to warrant the belief that both practices grew from the same conceptual framework. Indeed, the full citation is substantially more nuanced and complex, and corrections were made to reflect her full argument. I appreciate her bringing this to my attention.

REFERENCES:

- Veith I (Translator). The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. University of California Press, 1st edition. 2002.

- Ernst E. Acupuncture – a critical analysis. J Intern Med. 2006; 259(2):125-137.

- Ramey D, Buell PD. A true history of acupuncture. Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2004;9:269-273.

- Dorfer L, Moser M, Spindler K, Bahr F, Egarter-Vigl E, Dohr G. 5200-year-old acupuncture in central Europe? Science. 1998;282(5387):242-243.

- Dorfer L, Moser M, Bahr F, et al. A medical report from the Stone Age? Lancet. 1999;354:1023-1025.

- Smith, GS, Zimmerman R. Tattooing Found on a 1600 Year Old Frozen, Mummified Body from St. Lawrence Island, Alaska. American Antiquity 40(4): 433-437. 1975.

- Garcia, Hernan and Antonio, Sierra. Wind in the Blood – Mayan Healing & Chinese Medicine. Redwing Books, 1999.

- Villoldo A. Shaman, Healer, Sage. Hamony Books, 2000.

- Lao Tzu (Author), Mair VH (Translator). Tao Te Ching: The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way. New York. Bantam Books. 1990.

- Whorton JC. Nature Cures: The History of Alternative Medicine in America. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Wu AS. Chinese Astrology. The Career Press, Inc. 2005.

- Lo V. The territory between life and death. Essay review. Med Hist. 2003 Apr;47(2):250-8.

- Walters D. Chinese Astrology. Aquarian Press. 1987.

- Pregadio F. Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China. Stanford University Press, 1st edition. 2006.

- Burkert W. Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 1972.

- Reid D. Chinese Herbal Medicine. Shambhala. 1987.

- Pas JF. Historical Dictionary of Taoism. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. 1998.

- Religion of Tao. Center of Traditional Taoist Studies. www.tao.org. Accessed September 2008.

- Fischer-Schreiber I. The Shambhala Dictionary of Taoism. Shambhala. 1st edition. 1996.

- Ware J. Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of A.D. 320. The Nei P’ien of Ko Hung (Pao-p’u tzu). Cambridge (Mass.): M.I.T. Press, 1966. Reprint. New York: Dover Publications, 1981.

- Holmyard EJ (editor) The Arabic Works of Jabir ibn Hayyan. New York, E. P. Dutton. 1928.

- Kingsley P. Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition. Oxford University Press. 1997.

- Copenhaver, BP (Editor). Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge. 1992.

- Reisch G. Margarita Philosophica, Hoc Est Habituum Sev Disciplinarum Omnium. Basileæ 1583.

- Jackson WA. A Short Guide to Humoral Medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Sep;22(9):487-9.

- Starr D. Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce. Knopf. 1st edition. 1998.

- Manilius M (author), Goold GP (Translator). Manilius: Astronomica. Harvard University Press. 1977.

- Epler DC Jr. Bloodletting in early Chinese medicine and its relation to the origin of acupuncture. Bull Hist Med. 1980 Fall;54(3):337-67.

- Alpher JV (Editor) Oriental Medicine: An Illustrated Guide to the Asian Arts of Healing. Serindia. United Kingdom, 1st Edition 1995.

- Hall H. Puncturing the Acupuncture Myth. Science-Based Medicine. Posted on October 21, 2008. Accessed November 2008. http://www.sciencebasedmedicine.org/?p=252.

- Unschuld PU. Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. University of California Press. 1988.

- Barnes LL. Needles, Herbs, Gods, and Ghosts: China, Healing, and the West to 1848. Harvard University Press. 2005.

- Kim HB. Handbook of Oriental Medicine. Harmony & Balance Press; 3rd Edition. 2007.

- Andrews BJ. History of Pain: Acupuncture and the Reinvention of Chinese Medicine. APS Bulletin. May/June 1999;9(3). 5.

- Unschuld PU: The past 1000 years of Chinese medicine. Lancet Suppl SIV9:354, 1999.

- Skrbanek P: Acupuncture: Past, present and future, in Stalker D, Glymour C (editors): Examining Holistic Medicine. Buffalo, NY, Prometheus Books. 1985.

- Ma KW. The roots and development of Chinese acupuncture: from prehistory to early 20th century. Acupunct Med 1992;10(Suppl):92-9.

- Andrews B. Tailoring Tradition: The Impact of Modern Medicine on Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1887-1937. In Alleton V and Volkov A (editors). Notions et Percpetions du Changement et Chine. Paris: Collège de France, Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises. 1994

- Taylor K. Chinese Medicine in Early Communist China, 1945-63; A Medicine of Revolution, RoutledgeCurzon, 2005.

- Scheid V. Chinese Medicine in Contemporary China: Plurality and Synthesis. Duke University Press, 2002.

- Schram SR. The Political Thought of Mao Tse-Tung. New York: Praeger Publishers. 1969.

- Basser S. Acupuncture: a history. Sci Rev Altern Med 1999;3:34-41.

- Ernst E, White A, eds. Acupuncture: A Scientific Appraisal. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann. 1999.

- Ernst E. The recent history of acupuncture. Am J Med. 2008 Dec;121(12):1027-8.

- Ernst E. Complementary medicine: the facts. Phys Ther Rev 1997;2:49-57.